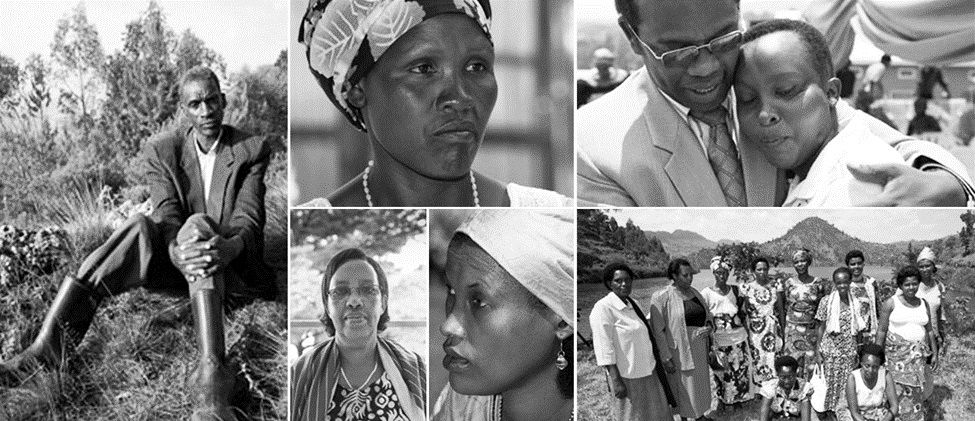

Photo: Courtesy

Literally, everyone might be aware of the very painful tragedy that lies in the heart of Rwanda’s history, a hard story to narrate, as it triggers the collective memory of its people. The 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi which left scars that run deep, wounds that still bleed decades later. Among the countless horrors, one silent plight remains often overlooked—the children born from genocidal rape.

These children, innocent victims of unspeakable atrocities, are the offspring of violence and hatred, their existence a constant reminder of the darkest days in Rwanda’s past according to their mothers. For many, their identities are shrouded in ambiguity, their fathers unknown or, worse, known as the very perpetrators who tore their families apart.

In the face of such unimaginable suffering, organizations like SURF and Foundation Rwanda have been beacons of hope, extending a lifeline to these marginalized individuals. They have provided essential support, from education to mental health services, bridging the chasm of neglect and stigma that surrounds them. However, despite their invaluable efforts, significant gaps remain, echoing the persistent cries of those still in need.

One may wonder what needs to be done by Rwanda as a nation committed to healing and reconciliation. That is to step forward and fulfil its duty to the second generation. If the government may enact comprehensive measures to address the multifaceted challenges faced by children born from genocidal rape and their mothers, that can ease and heal some unseen wounds.

First and foremost, mental health services need to be made accessible and tailored to the unique needs of these children mothers-survivors and their offspring-children. With a preference of anonymity, the source/second-generation born from rape said, “Trauma runs deep in our veins, a legacy of pain passed down through generations, from our mothers to us straight. By investing in counselling, therapy, and psychosocial support, Rwanda can provide the healing balm needed to mend our fractured souls and rebuild shattered lives.”

Mother and son who was born from rape in the 1994 Genocide against Tutsi – Photo: Courtesy

Education is another cornerstone of empowerment for these vulnerable individuals. Many children born from genocidal rape face barriers to education, perpetuating cycles of poverty and exclusion as Ines Kayitesi (changed the name due to the source personal reasons) “SURF (Survivors Funds) and Foundation Rwanda has done a lot, but the government can also support us by implementing targeted initiatives to ensure their access to quality schooling, including scholarships, mentorship programs, and specialized educational support.”

According to their mothers, physical health concerns cannot be overlooked either. Many survivors and their children suffer from health issues stemming from the trauma of their past, exacerbated by limited access to healthcare. Some women were raped by multiple men and infected them with HIV/AIDS which resulted in infecting their children as well. By expanding healthcare services and establishing dedicated clinics for survivors and second-generation youth, Rwanda can address their medical needs and promote overall well-being.

Moreover, stigma remains a pervasive force, casting a shadow over the lives of survivors and their children born from rape. By launching nationwide awareness campaigns to challenge stereotypes and promote acceptance and inclusion, Rwanda will then become a better country in regards to unity and reconciliation as MINUBUMWE always strive for that. Also by fostering a culture of empathy of understanding, the government can pave the way for a society where every individual is valued and embraced.

The survivors are still bleeding from unseen wounds from the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi. Photo: Courtesy

In all these endeavours, the voices of survivors and their children must be elevated and empowered. They are not passive recipients of aid but resilient agents of change, capable of shaping their own destinies. Rwanda must involve them in decision-making processes, ensuring that their perspectives guide policies and programs for their benefit. After all, they are grown-ups now, they are 29 years old and they are good at playing parts in the country’s development as well.

To sum it up, the journey toward healing and reconciliation is one that Rwanda must undertake together, as a nation united in its commitment to justice and compassion. By standing in solidarity with survivors and their children born from rape in the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi, Rwanda can rewrite the narrative of its past, turning the page on tragedy and ushering in a future of hope and resilience.

End!!!