In the early morning mist of Nyagatare District, Rwanda, a group of students can be seen walking silently along a red dirt road. Their shoes are dusty, their uniforms slightly worn, and their backpacks carry not only books but also the weight of hope.

These children are headed to Rugarama Primary School, one of the many rural schools in East Africa that continue to battle systemic challenges in delivering quality education. While the world celebrates advancements in technology, digital learning, and educational equity, the reality for many rural teachers and learners tells a different story. This is not just a story of hardship—it is also a story of resilience, sacrifice, and the urgent need for change.

Morning shadows and long distances

For 14-year-old Aline, a student in Primary Six, the school day starts before the sun rises. She wakes up at 5:00 a.m., helps her mother fetch water from a nearby valley, and prepares breakfast for her two younger siblings. Then, she begins her two-hour walk to school. The journey is neither easy nor safe.

“There are times when it rains heavily, and the roads become muddy and slippery. Sometimes, I arrive at school wet and cold,” she explains. “But I must come because I want to become a nurse one day.”

Like Aline, many students in rural areas travel long distances on foot; some even cross rivers or thick forests to reach the nearest school. The lack of transportation infrastructure in remote areas is a primary barrier to access. For those who manage to arrive, the school itself often lacks basic amenities: no electricity, no clean drinking water, and sometimes no proper toilets.

The battle with limited resources

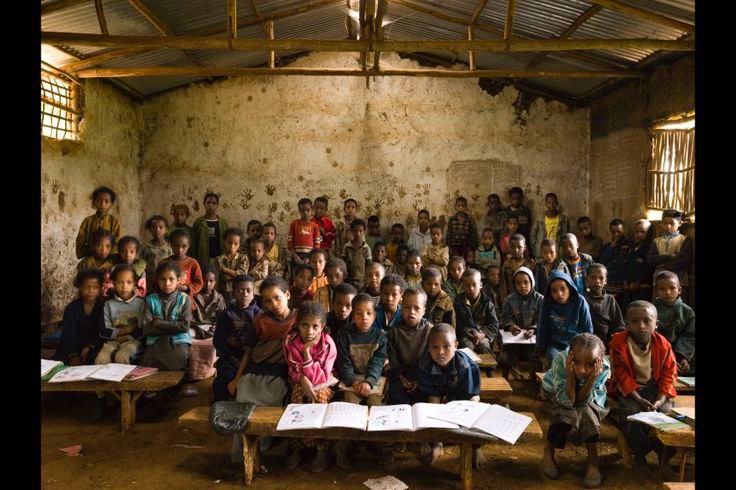

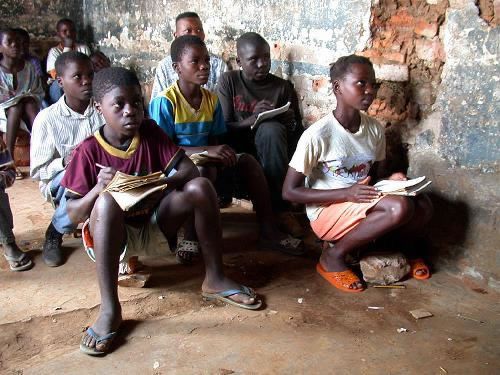

Classrooms in rural schools often consist of nothing more than bare cement floors and worn-out blackboards. Students share textbooks in groups of five or more. Exercise books are a luxury, and pens are reused until the ink runs dry.

In one classroom in the Gicumbi District, a blackboard hangs crookedly against a cracked wall. The teacher writes math equations with a half-used piece of chalk. Students peer from behind wooden benches, trying to copy notes into their shared notebooks. There is no projector, no internet, and certainly no computers.

“In urban schools, students are learning computer science and coding,” says Headteacher Alice Uwimana of a rural primary school. “Here, our children haven’t even seen a real computer.”

The digital divide is a major concern. While the world moves toward digital learning, many rural students are left behind. Lack of electricity, internet connectivity, and trained ICT teachers means digital literacy is a dream that remains out of reach.

Girls are at greater risk

For girls in rural schools, the challenges are even more profound. Cultural norms, household responsibilities, and early marriage continue to affect their education.

“I dropped out of school when I was 13 because I got pregnant,” confesses a young mother named Claudine from Bugesera. “There was no one to talk to about reproductive health. We were ashamed to ask.”

Menstrual hygiene management is another barrier. Many rural schools lack private toilets or access to sanitary pads. As a result, girls often miss school during their periods, which affects their academic performance.

Efforts to empower girls must go beyond slogans. They require concrete interventions such as gender-sensitive facilities, health education, and mentorship programs that support girls to not just stay in school, but thrive.

Language barriers and learning gaps

In rural Rwanda, the shift from Kinyarwanda to English as the language of instruction in upper primary and secondary has created significant challenges. Many students struggle to grasp lessons taught in English, especially in science and math.

“The students don’t understand the questions in national exams,” says Mr. Habimana, a science teacher. “Even if they know the answer, they don’t know how to express it.”

Teachers, too, are affected. Many were trained in French or Kinyarwanda and have limited proficiency in English. This results in poor lesson delivery, translation errors, and a lack of confidence in teaching core subjects.

This language gap further widens the performance gap between urban and rural schools. Students in cities often have access to English-speaking tutors, books, and media. Rural students, on the other hand, are often limited to what they hear in the classroom.

Mental health and motivation

One of the silent challenges in rural education is the emotional burden carried by both students and teachers. Poverty, malnutrition, and family instability create stress and anxiety among learners. Many come to school hungry, tired, or ill.

Teachers, too, face emotional exhaustion. The pressure to produce results with limited resources leads to burnout. Some suffer from depression or hopelessness, especially when their efforts go unrecognized.

“There are days I feel like giving up,” says Ms. Jacqueline, a primary school teacher in Rusizi. “But then I remember that even if I can help just one child succeed, it is worth it.”

Mental health support is rarely available in rural schools. There are no counselors or psychologists. Training teachers in basic psychosocial support could be a small but important step in improving the emotional well-being of both learners and educators.

Education is a fundamental right. And yet, for millions of students in rural schools, it remains a daily struggle. The challenges they face, like distance, poverty, lack of resources, teacher shortages, and gender inequality, are immense but not insurmountable.

What is needed is commitment. From policymakers, educators, communities, and international partners. Rural schools do not need charity; they need equity. They need the same quality of teachers, facilities, and opportunities as urban schools.